Reading the Bible Anew The Lord’s Supper Part Two :

What is the Meaning of “This Is My Body”?

“Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink His blood, you have no life in you… For my flesh is true food and my blood is true drink.” I think you would agree with the disciples that this is a hard saying. Though this quotation from John does not include a narrative of the institution of the Lord’s Supper, it is seen as a theological reflection on the Lord’s Supper. So, what exactly does it mean to partake of bread that Christ himself said is His Body? Can we partake acceptable to Christ unless we know how to answer this question? Paul states “whoever eats the bread or drinks the cup in an unworthy manner will be guilty of sinning against the body and blood of the Lord.”

There are many doctrinal interpretations to this question. The answer fundamentally depends on the hermeneutical principal one uses. The early church fathers used a literal, realistic, and ecclesial interpretation. The church tradition guided by the Spirit safeguards interpretation. Ignatius of Antioch—a disciple of John- ( 110 AD) held that to eat the bread was to “partake” of Christ’s flesh. Justin Martyr (150 AD) said that “not as common bread.. but by the prayer of His Word is the flesh and blood of that Jesus.” Augustine of Hippo ( 354-340 AD) had a nuanced approach. By believing in Christ, the believer receives the life-giving benefit of Christ’s flesh which the external eating of the bread signifies. Thus, it is a sacrament that contains the sign it signifies. By eating one becomes united with Christ. The Roman Catholic interpretation is at the moment of consecration the bread actually becomes Christ’ flesh. This view was solidified by Thomas Aquinas and codified by Council of Trent (1215) and given the formal name of transubstantiation. For Eastern Orthodox the interpretation leaves “how” it turns into actual flesh as a mystery.

The Lutheran interpretation is also “literal” with Luther refusing to say “is” can mean signifies. Therefore, this interpretation is similar to the Catholic. It is, however, a sacramental union. The Catholic view is an actual change to the physical where Luther would say when one eats the consecrated bread, one truly eats Christ’s body (though invisibly and supernaturally). This eating conveys Christ’s forgiveness and life to the believer.

The Reformed interpretation differs depending on the source. John Calvin (1509–1564) rejected both the Catholic concept of eating the physical body and the concept of it being just a memorial. Instead, he believed it is a real feeding of the body by faith through the Holy Spirit. The Westminster Larger Catechism (a Reformed statement, 1647) summarizes this view: in the Supper, worthy receivers “do therein feed upon the body and blood of Christ, not after a corporal or carnal manner, but in a spiritual manner; yet truly and really, while by faith they receive and apply unto themselves Christ crucified and all the benefits of His death.” Christ’s presence is there but not in the elements.

Huldrych Zwingli ( 1484-1531), the founder of Reformed theology, returned to the bible as a blueprint or pattern for imitation and restorationist understanding of church renewal. He saw the bible as a normative pattern for all walks of life. He believed everything not based on scripture must be abolished. The cry was for “scripture alone.” In interpretation of John’s scripture, he notes that Christ spoke metaphorically e.g “I am the door”; “I am the vine.” Therefore, the Lord’s is a memorial meal in which we remember Christ’s death and give thanks for His once-for-all sacrifice. The Lord’s Supper proclaims the gospel. This is clearly an antecedent to Church of Christ understanding.

The Evangelical (Baptists, non-denominational, Pentecostal, etc.) view is descended from Zwingli. This view can be summarized by the Faith and Message (2000) of the Southern Baptist Convention: The Supper “ is a symbolic act of obedience whereby members of the church….memorialize the death of the Redeemer and anticipate His second coming.” It is an “ordinance” not a sacrament. The emphasis is on “Do This in Remembrance of Me” and on personal self-examination and gratitude.

The Restoration Movement led by Alexander Campbell and Barton W. Stone had a slightly different view. The Lord’s Supper is “emblematic of the Lord’s sacrifice and commemorative of His death.” The bread and wine are just emblems to engage us in the reality of the gospel. There is one other important interpretative point: “In the Lord’s Supper especially does God commune with sons and daughters and they with Him.” Christ is present at this memorial among the worshipers. He criticized those who made it a somber occasion and instead that it is a joyous “festival” of unity and thanksgiving. His interpretation was thus symbolic (emblematic ) and memorial. Barton W. Stone emphasized the unity of believers in the Supper. “ The body of Christ, crucified on Calvary, is represented in the one bread and one loaf and Christians unified in one body are joint partakers of it. The language of communion was understood as fellowship with Christ and among the believers. Unlike Campbell he insisted on unleavened bread. Both celebrated the Lord’s Supper on the Lord’s Day.

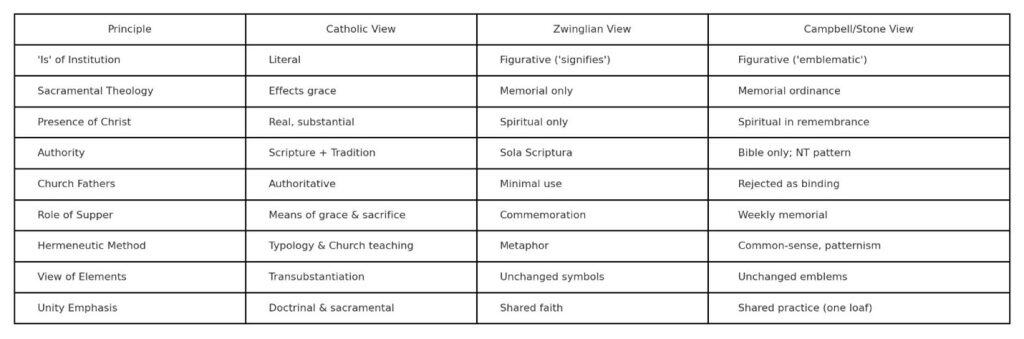

The following chart summarizes the differences between the Catholic, Zwingli, and Restoration approaches to interpreting the meaning of the bread being “the body of Christ.”

Reference List

[1] Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1997, §§1333–1377.

[2] T. Aquinas, Summa Theologica, III, q.75, a.1–4, translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province.

[3] Council of Trent, Session XIII, Doctrine on the Eucharist, 1551.

[4] Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Smyrnaeans, Ch. 6–7, ca. A.D. 110.

[5] Justin Martyr, First Apology, Ch. 66–67, ca. A.D. 155.

[6] Irenaeus of Lyons, Against Heresies, Book V, Ch. 2, ca. A.D. 180.

[7] Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures, Lecture 22, ca. A.D. 350.

[8] J. Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book IV, Ch. 17, 1559.

[9] U. Zwingli, Fidei Ratio, 1530.

[10] W.P. Stephens, Zwingli: An Introduction to His Thought, Oxford University Press, 1992.

[11] B. Gordon, Zwingli: God’s Armed Prophet, Yale University Press, 2021.

[12] A. Campbell, The Christian System, Bethany, VA: A. Campbell, 1839.

[13] A. Campbell, “On the Breaking of Bread,” Millennial Harbinger, vol. 3, 1832.

[14] B. W. Stone, “The Lord’s Supper,” The Christian Messenger, June 1834.

[15] S. Hahn, The Lamb’s Supper: The Mass as Heaven on Earth, New York: Image, 1999.

[16] Westminster Confession of Faith, Ch. 29, “Of the Lord’s Supper,” 1646.

[17] R. C. Sproul, What is the Lord’s Supper?, Reformation Trust Publishing, 2013.

[18] B. Witherington III, Making a Meal of It: Rethinking the Theology of the Lord’s Supper, Baylor University Press, 2007.

{19} Allen, L and Hughes, R.T. Discovering Our Roots- The Ancestry of the Churches of Christ. Abilene, ACU Press